Standing at a busy crossroads, at rush hour, I looked up at the towering magnificence of Genoa’s Medieval Porta Soprana. This fleeting glimpse, before the traffic lights changed and the roar of the contemporary city struck up again, impressed me with a sense of the power, protection and wealth of this Republic, dubbed ‘the Proud’. I had been finding glimpses of Genoa’s Medieval and Early Modern past hard to come by. Architecturally, the city is dominated by eighteenth-, nineteenth- and twentieth-century developments. Earlier treasures are tucked away, like the Renaissance masterpiece, the strada nuova. I have spent the last ten years working on the history of Renaissance Venice, ‘the most serene’ Republic. Beyond the realisation that I was developing the habit of working on cities, the epithets of which made them sound like protagonists of C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I found that I had become accustomed to researching a city within which a created sense of the past was given up much more readily. Naturally, the challenge for historians is to move beyond these first appearances but in Venice, unlike Genoa, historical imagination is not difficult to generate.

These two cities provide a potentially rich comparison but have very different histories and historiographies. After a series of wars during the fourteenth century, Venice is considered to have eclipsed its formal rival, reaching the zenith of its political and economic power during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It was only in the seventeenth century that Genoa developed considerable wealth as a result of its role in international banking, at a time when Venice is considered to have started its economic ‘decline’. Historical writing about the two cities is also contrasting: copious and effusive for Venice and more limited and, at times, apologetic for Genoa. In the case of the latter, the historiography has been developed almost entirely by local historians and, where the city is given attention in general collections on Renaissance Italy, the aim of the authors appears to be to explain developments that took place in spite of the wider political context – characterised by local unrest and foreign dominance. Carlo Bitossi has described Genoa’s lack of Renaissance panegyric tradition, intimating that Genoa has developed an historiographical anti-myth without a myth. The same could not be said of Venice. Here, the myth and dominant tone of the historiography makes it seem almost literally natural that the self-styled ideal, godly Republic would have developed sophisticated structures in a number of different spheres, including that which particularly interests me – charity and public health. For all of the apparent contrasts in their political contexts, Genoa developed many of the same initiatives. Part of my new research project, entitled ‘Cleaning Up Renaissance Italy’ will explore why that was.

One commonality between these cities was the port environment. The Genoese government body with responsibility for public health, the Padri del Comune, invariably cited the aim of protecting the port in their explanations of measures to develop street cleaning or interventions in the natural environment of Genoa and its wider Ligurian state. In written and visual traditions, the port is celebrated as one of the sources of the city’s wealth, a ‘gem’, a place of refuge. In the ninth century, the relics of Saint Romulus had been brought to Genoa from Sanremo in order to protect them, it was said, from the threat of pirates. The same language of protection was used throughout the following centuries and in different contexts, for example, in relation both to the treatment of merchandise and to the attitudes of the city’s governing bodies to foreign communities – including German, Greek, Jewish and Spanish – as the population became increasingly cosmopolitan.

Historians have often characterised the use of space in Italian cities as becoming distinguished by zones through the Medieval and Renaissance periods and the tendency has been to try to identify increasingly defined central and peripheral areas. In Venice, the city’s parishes included a cross section of social groups but solutions to social and medical problems became increasingly spatial; it was here that the first Ghetto was famously established in 1516. In Genoa, the strong tradition of alberghi meant that the division of urban space was primarily directed by family ties, although, in the sixteenth century, the strada nuova did link noble houses. It was not until 1660 that the government required the Jewish population to live within a Ghetto, reputedly as a result of tensions in the aftermath of the severe plague of 1656. Before then, formal quarters or institutions do not seem to have been allocated to foreign populations. Ennio Poleggi has illustrated that occupational clusters existed, such as that for shipbuilding around the Molo, but Genoa’s polycentric nature makes it difficult to characterise areas as central or peripheral. The place of foreign communities within Genoa’s cityscape and society is hard to pin down.

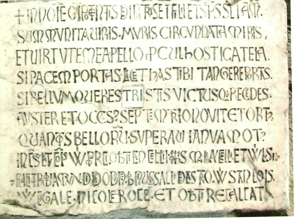

An insight into the official attitudes toward these communities in Medieval and Renaissance Genoa can be gleaned from an inscription on the Porta Soprana – the gateway with which we started. Said to have been built by a communal effort which bordered on the miraculous in the face of the political and military threat of Federico Barbarossa during the twelfth century, the gate includes a Latin inscription which welcomes those who seek peace and repels those who approach the gateway in the name of war. The strong communal tradition which built the walls of the city also prioritised the protection of the port and the city’s trading economy. Foreign communities were accepted into the city because of their valuable contribution and they were said to be more than tolerated: a recent exhibition at the city’s Medieval hospital, the Commenda di Prè, reflected this with its title, ‘No one feels a stranger in Genoa’. Of sixteenth-century Venice, it was famously said that the city played host to the people of the world. The parallels between these two ports – particularly in relation to their societies and environments – may prove easier to find than it first seemed.

Jane Stevens Crawshaw