A dense work of early English prose, strewn throughout with serious and teasing marginalia from its author, might not be the most likely candidate for stage adaptation – but this project has just been undertaken by a team of artists and academics in Sheffield. William Baldwin’s Beware the Cat, written in 1553, will be performed in September as part of the university’s 2018 Festival of the Mind.

As a literary form, the novel is usually thought to have developed in the 18th century with the mighty classics Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe and Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne. But researchers believe we should be looking back to the relatively neglected prose fictions of the Tudor era to find the earliest English examples. Beware the Cat, an ecclesiastical satire about talking cats, is a prime candidate and is now thought to be the earliest example of the novel form in the English language.

Baldwin is barely known outside the circles of Renaissance literature, but he was highly celebrated and widely read in Tudor England. In the mid-16th century, he was earning an inky-fingered living as a printer’s assistant in and around the central London bookmaking and bookselling area of St Paul’s Cathedral. As well as writing fiction, he produced A Mirror for Magistrates, the co-written collection of gruesome historical poetry that was highly influential on Shakespeare’s history plays. He also compiled a bestselling handbook of philosophy, and translated the controversial Song of Songs, the sexy book of the Bible.

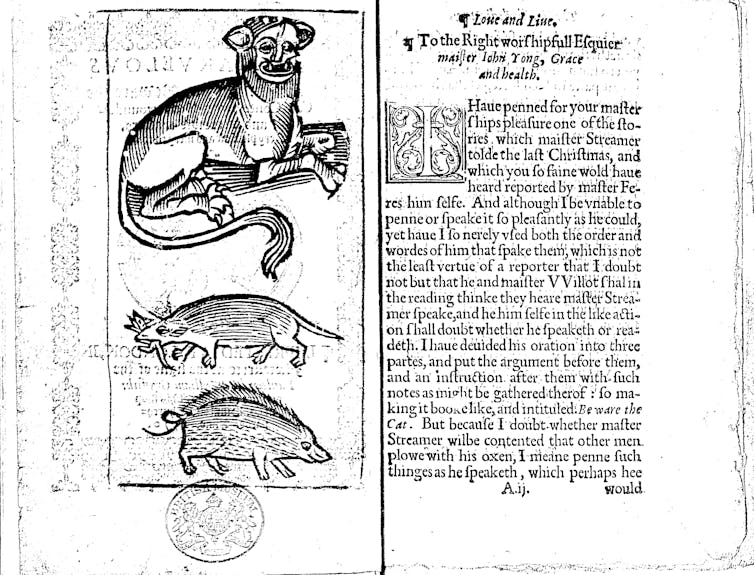

Beware the Cat tells the tale of a talkative priest, Gregory Streamer, who determines to understand the language of cats after he is kept awake by a feline rabble on the rooftops. Turning for guidance to Albertus Magnus, a medieval alchemist and natural scientist roundly mocked in the Renaissance for his quackery, Streamer finds the spell he needs. Then, using various stomach-churning ingredients, including hedgehog’s fat and cat excrement, he cooks up the right potion.

And it turns out that cats don’t merely talk – they have a social hierarchy, a judicial system and carefully regulated laws governing sexual relations. With his witty beast fable, Baldwin is analysing an ancient question, and one in which the philosophical field of posthumanism still shows a keen interest: do birds and beasts have reason?

Turbulent times

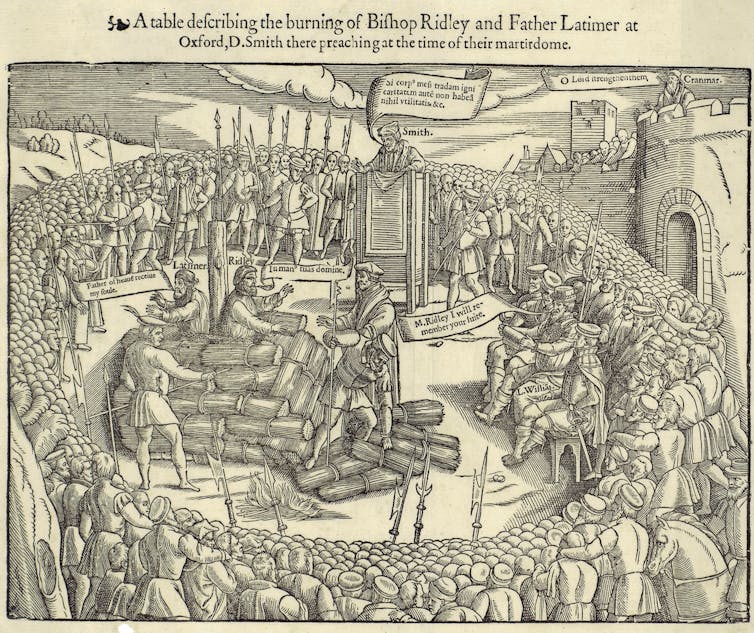

But rights and wrongs of a different order coloured Baldwin’s book release. He self-censored for several years before making the work public. Beware the Cat was written in 1553, months before the untimely death of the young Protestant king, Edward VI. Next on the throne (if you disregard the turbulent nine-day reign of Lady Jane Grey) was the first Tudor queen, Mary I. Her Catholicism was fervent and these were terrifying days. By the mid-1550s, Mary was burning Protestant martyrs. One of her less alarming, but still consequential, decisions was to reverse the freedoms accorded the press under her brother Edward.

At the height of his power during the 1540s, the Lord Protector during the young Edward’s reign, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, had relied on particular printers to spread the regime’s reformist message. Men such as John Day (printer of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs) and Edward Whitchurch – Baldwin’s employer – printed and circulated anti-Catholic polemic on behalf of the state. Not content to persecute these men by denying them the pardon she accorded other Protestant printers, Mary I banned the discussion of religion in print unless it was specifically authorised by her officials.

Radical press

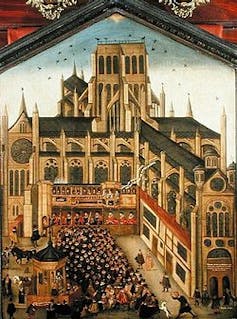

As a print trade insider, Baldwin was intimately connected with the close community of this radical Protestant printing milieu – and Beware the Cat is deliberately set at John Day’s printing shop. Having written a book that parodies the Mass, depicts priests in some very undignified positions and points the finger at Catholic idolatry, Baldwin thought better of releasing it in the oppressive religious climate of Mary’s reign. But by 1561, Elizabeth I was on the throne and constraints on the press were less severe – despite the infamous case of John Stubbs, the writer who in 1579 lost his hand for criticising her marriage plans.

Baldwin, now in his 30s, had become a church deacon. He was still active as a writer and public figure, working on his second edition of A Mirror for Magistrates and preaching at Paul’s Cross in London, a venue that could attract a 6,000-strong congregation.

Once it was released, Beware the Cat went through several editions. It was not recognised for the comic gem that it is until scholars such as Evelyn Feasey started studying Baldwin in the early 20th century and the novel was later championed by American scholars William A. Ringler and Michael Flachmann.

Now, it has been adapted for performance for the first time and is being presented as part of the University of Sheffield’s Festival of the Mind. This stage version of Beware the Cat has been created by the authors with Terry O’Connor (member of renowned performance ensemble Forced Entertainment) and the artist Penny McCarthy.

Baldwin’s techniques of embedded storytelling, argument and satirical marginalia are all features that have been incorporated into this interpretation of the text. The production also includes an array of original drawings (which the cast of four display by using an onstage camera connected to a projector), but none of the cast pretends to be a cat. Instead, it is left to the audience to imagine the world Baldwin’s novel describes, in which cats can talk and – even if just for one night – humans can understand them.

Rachel Stenner, Lecturer in English Literature 1350-1660, University of Sussex and Frances Babbage, Professor of English Literature, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.