In May 2016 it was reported that the number of vegans in Britain had risen by 360% in ten years.1 A Guardian article, published in November 2018, indicated that this number will continue to increase in the coming years, with one in eight Britons now identifying as vegetarian or vegan, and 21% claiming to be ‘flexitarian’ (a vegetable-based diet that occasionally includes meat).2 In 2016, Counterpoint published a report entitled ‘Compassionate Consumption: How Veganism is Taking Over Western Europe’ (2016), which suggested that increasing numbers of Western Europeans are rejecting animal products due to an ethical concern for animal rights.3 The report also argued that the sudden rise in veganism has largely been spurred on by key documentaries, such as Live and Let Live (2013) and Earthlings (2015), which attempt to give animals a voice and expose their suffering at the hands of humans.4 These documentaries may find a surprising counterpart in George Gascoigne’s early modern hunting manual, The Noble Arte of Venerie or Hvnting (1575, second edition printed 1611).5

The Noble Arte of Venerie (a loose translation of Jacques du Fouilloux’s 1573 French hunting manual La Vénerie), has received considerable critical attention in recent years due to the inclusion of four poems that give a voice to animals commonly pursued in the hunt –– that of the hart, the hare, the otter and the fox.6 It is difficult to ascertain the intention of these poems, let alone their impact on early modern conceptions of animal welfare, but the manual is unique in asking its readers to consider the feelings of these four animals. In this way, The Noble Arte of Venerie can be compared to twenty first century documentaries which ask their viewers to rethink their consumption of animal products. The poems may also provide a source of reflection for the current debates surrounding the enforcement of, and proposals to repeal, the 2004 Hunting Ban.7 Although it is unlikely that Gascoigne was a spokesperson for vegetarianism, let alone veganism, this article considers whether he was similarly asking his readers to show some compassion towards the animals they hunted, killed and consumed.

In the early modern period, hunting was justified by the assumption that man had complete authority over nature. This anthropocentric view was derived from the Bible, which stated that God granted man ‘dominion ouer the fish of the see, and ouer the foules of the ayre, and ouer all the beastes that crepe upo[n] the earth’ (Genesis 1.28).8 After the flood this power was increased when God informed Noah: ‘Every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you’(Genesis 9.2). Consequently, the consumption of animals was represented as a God-given right in the period and, as Erica Fudge has shown in her work on purity and meat-eating, although there were vegetarians, a meat-free diet was considered ‘bizarre.’9

As a favoured pastime of royalty and the English aristocracy, the hunt was also seen as an ennobling activity. However, the Forest and Game Laws, which restricted hunting to a privileged few, were a source of significant social tension because common people wanted the right to hunt for themselves, both for the purposes of leisure and food. In response to these laws, there were numerous incidents of poaching throughout the period. Admittedly these were largely acts of social rebellion, but poaching was at least partly carried out in order to obtain sustenance.10 Such acts conflicted with the high culture of the Elizabethan hunt which viewed “hunting for the pot” as vulgar. Indeed, sumptuous banquets usually accompanied hunting trips, compounding the pleasure taken in the chase and the status of those that partook in the sport. The poems included in The Noble Arte of Venerie pointedly criticise the enjoyment taken in hunting animals and the excessive consumption that occurred during the accompanying feasts, contrasting the insatiable greed of those in attendance with the temperance exhibited by animals.

The Renaissance scholar Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa was an ardent opponent of the hunt precisely on these grounds, and asserted in The Vanity of Arts and Sciences (1676) that hunting was only justifiable if ‘[n]ecessity should be occasions of its Commendations’; to support this viewpoint, Agrippa gave the examples of when ‘Meleager flew the Caledonian Boar not for his own pleasure, but to free his country from a common Mischief. So Romulus hunted Deer not for pleasures-sake, but to get food.’11 Gascoigne similarly criticised the hunt for its lack of necessity through the two poems, ‘The wofull words of the Hart to the Hunter’ and ‘The Hare, to the Hunter,’ which challenge claims that these animals are killed because they are harmful or profitable to humans. The hart asks:

Must thou therefore procure my death? for to prolong

Thy lingryng life in lustie wise? alas thou doest me wrong.

Must I with mine owne fleshe, his hatefull fleshe so feede,

Whiche me disdaynes one bitte of grasse, or corne in tyme of neede?

Alas (Man) do not so, some other beastes go kill,

Whiche worke thy harme by sundrie meanes: and so content thy will.

Which yeelde thee no such gaynes, (in lyfe) as I renew

When from my head my stately hornes, (to thy behoofe) I mew.12

Similarly, the hare laments:

But I poore Beast, whose feeding is not seene,

Who breake no hedge, who pill no pleasant plant:

Who stroye no fruite, who can turne vp no green,

Who spoyle no corne, to make the Plowman want:

Am yet pursewed with hounde, horse, might and mayne

By murdring men, untill they haue me slayne.13

It is important to note that in ‘The wofull words of the Hart to the Hunter,’ the hart acknowledges that its flesh does provide necessary sustenance for humans but claims it is more profitable when left alive. The hare in contrast states that it is of little nutritional benefit as its flesh ‘Is neyther, good, great, riche, fatte, sweete, nor sounde.’14 Despite this claim, hares were a common source of protein in the early modern period. Considering the status of harts and hares as food sources, Gascoigne’s criticism does not appear to be aimed at meat-eating but rather at the ‘lustie’ pleasure humans take in ‘murdring’ –– a criticism which becomes more apparent in the poems of the otter and the fox, animals which were regarded as vermin and therefore inedible.

Killing animals that were viewed as destructive to human food sources was justified in the early modern period through laws such as The Preservation of Grain Act (first passed in 1532 by Henry VIII and enhanced by Elizabeth I in 1566), which made it compulsory for individuals to kill creatures that appeared on an official list of ‘vermin’ –– a term that continues to be used today to justify the hunting of animals, such as foxes and badgers.15 The Act was largely drawn up to counter food shortages and the spread of disease caused by population growth and a series of bad harvests. Due to their supposedly ravenous natures, the otter and the fox were listed alongside a number of other animals as vermin and regarded, as Mary Fissell has argued, as poachers of human food.16

In The Noble Arte of Venerie, the reader is informed that the otter will ‘destroy all the fishe in your pondes’ and ‘A litter of Otters, will destroy you all the fishe in a ryuer (or at least, the greatest store of them) in two myles length.’17 Comparably, the fox is described in Edward Topsell’s The Historie of Foure-Footed Beastes (1607) ‘as such a devouring beast that it forsaketh nothing fit to be eaten.’18 In relation to economic crisis, Fissell argues that ‘[v]ermin threatened the always tenuous balance between ease and hardship, satiety and starvation and enough and not enough.’19 Gascoigne profits from this tension and uses the poems of the otter and the fox to comment on the ruling elite, who butchered animals for pleasure and denied the common people the legal right to hunt for food. In so doing, Gascoigne places the blame on those who hold power, rather than on the animals that were made scapegoats for food shortages.

‘The Otters Oration’ challenges the anthropocentric view found in the Bible that ‘all that is, was made for vse of man,’ by warning that ‘The very Scourge and Plague of God his Ban, / Will lyght on suche as queyntly can deuise / To eate more meate, than may their mouthes suffise.’ This criticism of overindulgence is furthered in the poem through an extended comparison of human gluttony with the restraint practiced by animals:

The beastly man, muste sitte all day and quasse,

The Beaste indeede, doth drincke but twice a day,

The beastly man, muste stuffe his monstrous masse

With secrete cause of surfetting alwaye:

Where beasts be glad to feede when they get pray,

And neuer eate more than may do them good,

Where men be sicke, and surfet thorough foode.

Who sees a Beast, for savrie Sawces long?

Who sees a Beast, or chicke or Capon cramme?

Who sees a Beast, once luld on sleepe with song?

Who sees a Beast make vensone of a Ramme?

Who sees a Beast destroy both whelpe and damme?

Who sees a Beast vse beastly Gluttonie?

Which man doth vse, for great Ciuilitie.20

The repetition of ‘beastly man’ creates a direct comparison between human and animal, collapsing the boundary that separates the two. This ‘beastly man’ does not describe humans in general but those who can afford to satisfy their appetites with luxurious and socially-specific dishes, for example venison, which was legally restricted to the ruling elite. Furthermore, the poem suggests that feasts, such as those which accompanied hunting trips, are ‘civilised’ occasions that paradoxically allow humans to satisfy their ‘beastly gluttonie.’

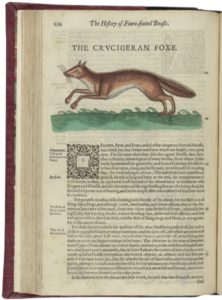

‘The Foxe to the Huntsmen’ extends the criticism of the ruling elite in a more direct manner. The poem’s speaker is identified as ‘Raynard the foxe,’ the medieval allegorical figure who was often represented as a peasant hero in stories which satirized the ruling elite –– a motif that is also found in Disney’s Robin Hood (1973) in which the eponymous character is represented by a wily fox.21 In Gascoigne’s poem, Raynard confesses that he is a greedy creature and agrees that ‘by his death […] al the farmers welth, may thriue & come to good’, as he will no longer prey upon their livestock. However, he goes on to assert that man is a ‘two leggd foxe’ who will ‘fliese a fee, / From euerie widowes flocke, a capon or a chicke, / A pyg, a goose, a dunghill ducke, or ought that salt will licke / Untill the widowe sterue, and can no longer giue.’ The poem also suggests that the humans who hunt foxes, ‘To kepe their neighbours poultry free, & to defende their flocks’, are hypocrites because they ‘spoyle, more profit in an houre, / Than Raynard rifles in a yere, when he doth most deuore.’22 The poem is clearly directed at those individuals who took advantage of the changing economic climate of the late 16th century in order to profit from both the land hunger and the rising prices of the time. By dehumanising those who prey upon the weak and vulnerable for their own benefit, identifying such humans as the true foxes, Gascoigne undermines the conventional justification of hunting animals that were conveniently labelled as vermin because they poach human food.

The poems of the hart, the hare, the otter and the fox, which are included in The Noble Arte of Venerie or Hunting, primarily express anger at the wider social and economic tensions of the period, but they also appeal for compassion for the animals that are hunted for leisure rather than for necessary sustenance, largely by revealing ‘master Man’ as the ‘moste bloudie beaste of all.’23 As with the twenty first century documentaries that advocate veganism, Gascoigne’s poems may not have convinced every reader to change their views on animal welfare but perhaps they caused some to question the pleasure taken in the hunt and the excessive consumption of animal products.

Nicole Mennell is a PhD Candidate at the University of Sussex and co-founder of ‘Brief Encounters’: an online peer-reviewed postgraduate jounal. An earlier version of this article appeared on Renaissance Hub, 4 (April 2017)