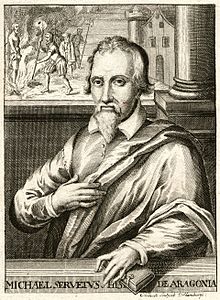

Michael Servetus (c. 1511-1553) was a renowned polymath, who is an important figure in the history of many disciplines. His nontrinitarianism led him to being condemned by Catholic authorities in France and, upon fleeing to Protestant Geneva, he was burnt at the stake for heresy. Despite his significance, until recently, there were no documents about him before 1531 and much of his biography is constructed from his declarations in trials before prosecutors. However, 13 new documents have been discovered, and they provide insight into this intriguing person and his education. Before he was 14, Servetus studied Latin Grammar (and its associated indirect disciplines: Rhetoric, Poetry and History) in the Studio of Sariñena, in Aragón. He then went on to study at Saragossa’s Studium Generale of Arts.

Michael Servetus (c. 1511-1553) was a renowned polymath, who is an important figure in the history of many disciplines. His nontrinitarianism led him to being condemned by Catholic authorities in France and, upon fleeing to Protestant Geneva, he was burnt at the stake for heresy. Despite his significance, until recently, there were no documents about him before 1531 and much of his biography is constructed from his declarations in trials before prosecutors. However, 13 new documents have been discovered, and they provide insight into this intriguing person and his education. Before he was 14, Servetus studied Latin Grammar (and its associated indirect disciplines: Rhetoric, Poetry and History) in the Studio of Sariñena, in Aragón. He then went on to study at Saragossa’s Studium Generale of Arts.

In 1477 the old Studium of Arts was granted permission to grant degrees in the Arts. The Head of the Studium was the Archbishop of Saragossa, but he almost never got involved in anything beyond choosing appointments. Grammar pupils were the majority of the Studium’s total number of students, which was at least 400 in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.The main building of the Studium was a large tower next to the walls of the city, whose three floors contained more than 20 chambers, latrines, a prison, a library and several main rooms for instruction.1 In 1520, Gaspard Lax, was appointed as High Master (Vice Chancellor) of the Studium, having previously been a professor at the University of Paris. The young Michael Servetus studied under Lax and three other teachers: Xerich, Ansías and Miranda. After Ansías and Miranda died, they were replaced by the physicians Villalpando and Carnicer. The young Servetus obtained his BA in 1523, and his MA the following year: in order to obtain his MA, Servetus had to serve as a support teacher. During these years he was educated in Latin Grammar, Natural Philosophy, Aristotelian Logic and Philosophy. Servetus was possibly also educated in Metaphysics and Astronomy and Arithmetic (Lax was a famous scholar in this discipline).

In the course of 1525/1526, Servetus was appointed one of the four principle tutors – the Masters of Arts – at the Studium. This meant he was in charge of a quarter of the Arts students, had associate teachers, and commanded a high salary. The four Masters of Arts of this Studium seemed to have coordinated some aspects of the Grammar education, for they were earning a part of the Grammar students’ fees. This may have inclined the Studium to Erasmus’s ideas. Lax himself seems to have been an Erasmian, and works by Erasmus were read in the Studium during those years. Servetus taught until at least January 1527, and the next month he travelled to Salamanca for unknown reasons. On March 28, 1527, when he was back in Saragossa, Servetus had a serious brawl with Gaspar Lax. This seems to be the reason Servetus had to leave Spain: he was expelled from the Studium, and Lax’s influence on his academic colleagues in every other Spanish University blocked Servetus securing a position in Spain. This situation also affected Servetus’s family in Aragón, who were cousins of Lax.2 During this conflict, the family apparently rejected the young Servetus, in favour of the celebrated Lax; this led to Servetus moving to Toulouse in France.

The new documents do not provide any direct information beyond 1527, though they give some hints on how Servetus got to the city of Toulouse, or Bologna. Above all the documents explain much of Servetus´ mastery of History and Geography, as shown by his 1534 Geography of Ptolemy. They also suggest how he gained competency in Geometry, Mathematics and Astronomy, which led to his complex predictions of the eclipses of Mars by the Moon and to being appointed as an Astrology teacher at the University of Paris (c. 1537). Thanks to completing his studies in Arts at Saragossa, he quickly became a student in Medicine. From these documents, we also learn where he gained his knowledge of Aristotelian Logic and Natural Philosophy, how he became fond of Erasmus, and specifically why he printed anonymously translations into Spanish of Latin grammatical treatises, and Spanish translations of works by Erasmus. Printed by his friend, Jean Frellon, and Frellon’s partners in Flanders, these translations echo what Servetus had been doing in the Erasmian Studium of Saragossa between 1520 and 1527.4

Miguel González Ancín & Otis Towns

[1] González Ancín, M., Towns, O (2017), Miguel Servet en España (1506-1527). Edición ampliada, Tudela, Imprenta Castilla, ISBN 978-84-697-8054-1. (Identical digital copy at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3093969 ), pp. 107-188.

[2] Ibid., pp. Our research suggests this family is actually an adoptive family, and that the true father was the physician master Nicholas de Villanueva, in the village of Cascante in Navarre, near Tudela town, pp. 29-65, 259-264.

[4] González Echeverría, F.J. (2017), Miguel Servet y los impresores lioneses del siglo XVI, doctoral thesis, Spanish National Distance University, directors Carlos Martínez Shaw and Luis Jesús Fernández Rodríguez.González Echeverría, pp. 172-203. (Online version: http://e-spacio.uned.es/fez/view/tesisuned:ED-Pg-HHAT-Fjbgonzalez ) // González Echeverría, F. J. (2011), El amor a la verdad. Vida y obra de Miguel Servet, Imprenta Navarro y Navarro, Zaragoza, col. Gobierno de Navarra, Departamento de Relaciones Institucionales y de Educación del Gobierno de Navarra, pp. 235-273; Specially Servetus’s Dísticos morales de Catón (1543), his Librito sobre la construcción de las ocho partes de la oración (1549), or his Libro infantil de notas sobre la elegancia y variedad de la lengua Latina (1549). Also related to education of young Spanish students are his poetic work Retratos o Tablas (1543).