Despite the persistent belief that Christmas was effectively invented by the Victorians and barely bothered with by anyone before the 19th century, a bit of a delve into the literature of the 17th century yields much in the way of interesting Christmas-related curiosities.

Performance has a long association with Christmas, from medieval mummers plays to Henry VIII’s “guising” games to the Elizabethan masque. Even today we gather to watch Christmas specials of TV dramas and take our children to see pantomimes. A Jacobean masque which is particularly relevant to this blog is Ben Jonson’s Christmas his Masque performed 1616 but first published in the second edition of Jonson’s Workes (London: 1640). The masque features the personification of Christmas himself, “attir’d in round Hose, long Stockings, a close Doublet, A high-crownd Hat with a Broach, a long thin beard, a Truncheon, little Ruffes, white Shoes, his Scarffes, and Garters tyed crosse, and his Drum beaten before him”. Christmas is accompanied by his ten “sons and daughters” who present us with a beguiling glimpse into 17th century Christmas customs, some of which sound very arcane. Along with familiar “children” of Christmas such as Minced-Pie, Wassail and Gamboll (“like a tumbler, with a hoop and bells”) comes New Year’s Gift “In a blew Coat, serving-man like, with an Orange, and a sprig of Rosemarie guilt on his head, his Hat full of Broaches, with a coller of Gingerbread, his Torch-bearer carrying a March-paine, with a bottle of wine on either arme” and Baby-Cake “Dressed like a Boy, in a fine long Coat, Biggin, Bib, Muckender, and a little Dagger; his Usher bearing a great Cake with a Bean, and a Pease”. The “great Cake with a Bean” is in the same vein as the tradition of stirring a sixpence into a Christmas pudding – whoever finds it will receive good luck.

Carol is another custom mentioned by Jonson. A blackletter book entitled Christmas Carols (Printed by P. Treveris, London: 1528) published in 1528 reveals a typically pre-reformation focus on the acts of various Saints, particularly St Stephen. whose feast day is 26th December – hence the mention in Good King Wenceslas. One carol recalls his stoning in rather unpleasant detail:

The cursyd Iewes at the last

Stones at Stephan they gan cast

They bette hym and bounde hym fast

And made his body in foule aray

Blessyd Stephan we thee pray

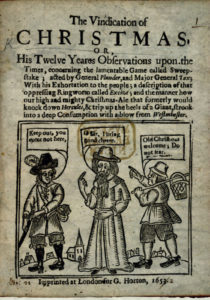

Another carol deals with the slaughter of the innocents by Herod. Over a century later, in the 17th century there appeared in 1642 a book called Good and true, Fresh and New Christmas Carols (Printed by E.P. for Francis Coles, London: 1642). These carols have a decidedly more secular feel to them, presumably eschewing any potentially risky associations with the perceived extravagances of the medieval church and its penchant for celebration. Even Jonson’s Christmas makes sure to point out that “I am no dangerous person, and so I told my friends o’ the Guard. I am old Gregorie Christmas still, and though I come out of Popes-head-alley, as good a Protestant, as any i’ my Parish.” Instead of focusing too intently on the religious elements of Christmas, carols such as All you that are Good Fellows, for example, tell of the generosity of the rich towards the poor. Christmas is praised as “a time of joyfulness, and merry time of year, When as the rich with plenty stor’d, doth make the poore good cheere;”. The carol refers to the Christmas custom of the rich “feasting” the poor – the apparent death of which is much bemoaned in pamphlets in the latter half of the 17th century. The carol relates that “Plum-porridge, Roast-beefe, and Minc’d-pies, stands smoking on the board, With other brave varieties,our Master doth afford”. The timing of the publication of the carol book is somewhat at odds with the message – in 1642 it is clear that not everyone was entirely sold on the idea of the beneficent and generous “Masters”. In fact, with the advent of the Civil Wars and subsequent protectorate, Christmas, famously “banned” by Oliver Cromwell due to its lack of Biblical precendent, became something of a political tool. A few Royalist propaganda pamphlets appeared playing on nostalgia for Christmas past and holding it up as a symbol of the proper social order, where tradition and nobility were respected. One such pamphlet is The Vindication of Christmas: His Twelve Years Observations upon the Times, concerning the lamentable Game called Sweep-stake: acted by General Plunder and Major General Tax (Printed for G. Horton, London: 1652). The tract is written from the point of view of Christmas, who states that “all Christians did, do and will celebrate it, and acknowledge it, for no Christian will blot or scrape christ’s day out of the calendar” and accuses the Puritans of “infusing heretical opinion into the hearts of the people, to wit (or with little wit) that plum-pottage was mere popery, and Roast beef Antichristian”. Christmas goes on to plead:

“may I say to England, what harm have I ever done unto you? I am sure I never persuaded you to be so uncharitable as to cut one anothers throats and to starve and famish the poor (as you have done continually)”

Christmas laments the terrible state of the country, where everyone is obsessed with wealth rather than charity, with money rather than religion. The pamphlet seems to play on nostalgia for an imagined time of celebration and generosity, where you could drop into a house and received some nice plum pottage and ale.

Even after the Restoration this nostalgia for the true meaning of Christmas didn’t go away. In a 1687 pamphlet called “Poor Robins hue and cry after Good House-Keeping, or, A dialogue betwixt Good House-Keeping, Christmas, and Pride”, “Poor Robin” rails against the erasure of festive hospitality, including feeding the poor (Printed for Randal Taylor, London: 1687). He claims that Pride has “made to fly the said Good-Housekeeping from his Ancient Habitations, and Places of residence, together with his old friend Christmas, with his four Pages, Roast-Beef, Minc’d-Pies, Plumb-Pudding, and Furmity, who used to be his constant Attendants, but now are grown so invisible they cannot be seen by poor People, nor good Fellows as formerly they used to be”. Hospitality and generosity towards the poor was the sadly lamented custom that was considered to have died out, nobody was serving up plumb-pudding (a meat and dried fruit stew) or furmity (a kind of wheat or barley porridge) anymore. One might be inclined to argue that complaining about how Christmas isn’t what it used to be is really the oldest Christmas custom of all.

This blog post was originally posted on Sussex CEMMS and was written by Maria Kirk, recent PhD and Associate Tutor at Sussex University.